As a Far East of Asian Researcher my focus on Japan is “Japanese Mythology” from 2013 till present time. I have worked with Portico Library in Manchester and registered as their researcher to develop my research by using their limited edition resources. I continued working on my research with Japan Society of North west (JSNW) till present.

I strongly believe that there is a big need for producing more works as both visuals, scripts and essays to raise the knowledge on Japanese Mythology which has an old strong root with the amazing history of Japan, which made it to be such an incredible nation. Japan always was one of the successful countries and I am really interested to show the West, specially UK, the depth of the history and specially the beauty of the ancient mythology such as Kojiki that unfortunately have never introduced well to the UK.

My mission is to make that bridge to show the importance part of Japanese Mythology and introduce depth of the history which will show why this country is so powerful and how the whole nation helped to achieve these successes which was not east and it has the incredible foundation of ancient stories.

My main research which I did not include here (because of copyright) looked deeply into mythology of Japan and what information of never been introduced that also are the b ig and important of Japan history and how it effects Japan’s culture in years till now.

I am also honoured and excited from the time I started this research to get to know more about Japan which leads me to start studying Japanese Language which I am in year one and it will support me and my research to access to more Japanese resources.

Please go to contact me if you have any questions or want to read my visual works and essays.

and now in below I put some of the works I did based on my Japanese research:

My previous research in 2012 was:

1) “Abstract Samurai Life”

( Visual essay of my art works on Samurai’s art based on my research on the Art of Samurai specially the story of “Tomoe Gozen”.)

Big part of my research at the moment is:

2) “Kojiki”

(That is my main part of my research and I started by “Amaterasu” and I produced my first test stop motion animation that is the link below

And also the effect of characters in Japanese culture and life style mostly animation and manga is very important to me. The depth of the each characters, their personality and stories has the big impact on the Japanese cinema and and media productions.

Working on Kojiki was so interesting for me and I love the powerful start of deities and the rest of the book make you believe the characters in a very strong way and it’s because each character have the good foundation of supernaturals which satisfied the curiosity in human nature.

One of the main characters I worked was “Amaterasu” which I put the link above to my visual production and her story.

I will update the blog with more news soon!

P.S Latest news on 2016 is planning for a Digital Innovative performance for Japan Day 2018 in Manchester based on Japanese Mythology. the meeting with Japan Society of North west (JSNW) and Mrs Yuko Howes took place which was positive. I will had few meetings with the director of Community Arts North West (CAN) in mid of September. Sara Domville which is the creative Producer for CAN will also loved the idea and she will join us to plan the funding application soon. I am really excited to take this project start in 2017 (probably May, will confirm it in 2 month) and also I had the opportunity to do two directing courses to enhance my directing and theatre production skills with HOME MCR, after discussing the idea of Digital Performance for Japan day and they were impressed and agreed to support me.

I invite you to have a look at some of the Mythology characters, and some part of my research which I saw that these are the available resources in English that unfortunately are not entirely correct and also Mrs Howes helped a lot to correct the parts which the stories were different from the actual original stories.

These articles and information are the best evidence and encourage for me to pursue my research to bring the correct and true original resources to show the amazing root and foundation of the Japanese history and mythology.

Japanese Mythology

- – Akki (Oni)

- – Gashadokuro

- – Ghidorah

- – Gojira

- – Kappa

- – Mothra

- – Ningyo

- – Rodan

- – Sennin

- – Shishi

- – Tengu

- – Yokai

- – Yurei

Akamataa

Oni (鬼?) are a kind of yōkai from Japanese folklore, variously translated as demons, devils, ogres or trolls. They are popular characters in Japanese art, literature and theatre.[1]

Depictions of oni vary widely but usually portray them as hideous, gigantic ogre-like creatures with sharp claws, wild hair, and two longhorns growing from their heads.[2] They are humanoid for the most part, but occasionally, they are shown with unnatural features such as odd numbers of eyes or extra fingers and toes.[3] Their skin may be any number of colors, but red and blue are particularly common.[4][5]

They are often depicted wearing tiger-skin loincloths and carrying iron clubs, called kanabō (金棒?). This image leads to the expression “oni with an iron club” (鬼に金棒 oni-ni-kanabō?), that is, to be invincible or undefeatable. It can also be used in the sense of “strong beyond strong”, or having one’s natural quality enhanced or supplemented by the use of some tool.[6][7]

Gashadokuro

Ghidorah

Gojira

Kappa

Ningyo

Ningyo is a Japanese water fairy who cries tears of pearls. Some say that Ningyo has the head of a human and the body of a fish. Other believe it is clad in sheer silk robes that move about it, like waves. Ningyos dwell in gorgeous palaces beneath the sea, and are very seductive.

refrence: http://www.mythicalcreaturesguide.com/page/Japanese+Mythology

From ancient times to the present, the Japanese people have celebrated the beauty of the seasons and the poignancy of their inevitable evanescence through the many festivals and rituals that fill their year—from the welcoming of spring at the lunar New Year to picnics under the blossoming cherry trees to offerings made to the harvest moon. Poetry provided the earliest artistic outlet for the expression of these impulses. Painters and artisans in turn formed images of visual beauty in response to seasonal themes and poetic inspiration. In this way, artists in Japan created meditations on the fleeting seasons of life and, through them, expressed essential truths about the nature of human experience.

This sensitivity to seasonal change is an important part of Shinto, Japan’s native belief system. Since ancient times, Shinto has focused on the cycles of the earth and the annual agrarian calendar. This awareness is manifested in seasonal festivals and activities. Similarly, seasonal references are found everywhere in the Japanese literary and visual arts. Nature appears as a source of inspiration in the tenth-century Kokinshu(Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems), the earliest known official anthology of native poetry (rather than Chinese verse). These poems, produced by courtiers who embraced a highly refined aesthetic sensibility, not only celebrated the sensual appeal of elements of the natural world, but also imbued them with human emotions. Melancholy sentiments, invoked by a sense of time passing, loss, and disappointment, tended to be the most common emotional notes. This attitude can be seen in such visual arts as Buddhist and Shinto paintings of the Heian period that include lovely but short-lived blossoming cherry trees. Autumnal and winter scenes and related seasonal references, such as chrysanthemums and persimmons growing on trees that have already lost their foliage, are eloquent expressions of this same sentiment.

A distinctive Japanese convention is to depict a single environment transitioning from spring to summer to autumn to winter in one painting. For example, spring might be indicated by a few blossoming trees or plants and summer by a hazy and humid atmosphere and densely foliated trees, while a flock of geese typically suggests autumn and snow, and barren trees evoke winter. (Because this convention was so common, seasonal attributes could be quite subtle.) In this way, Japanese painters expressed not only their fondness for this natural cycle but also captured an awareness of the inevitability of change, a fundamental Buddhist concept.

The confluence of Shinto and Buddhism in the use of seasonal references demonstrates the central position of this practice in Japanese culture. As indicated above, cherry blossoms can be found in pictures illustrating Buddhist as well as Shinto concepts, with both expressing the beauty and brevity of nature. Similarly, folding screens decorated with ink monochrome paintings showing a transition from one season to the next initially were placed in the private quarters of Buddhist monks. Ritual implements and decorative items used in Buddhist temples and practice are often covered with flowers, birds, and other scenes from nature.

While the pictorial compositions that encompass all four seasons together present a broad view, more compact versions also appear. During the Momoyama and Edo periods, seasonal flowers and plants such as plum blossoms, irises, and morning glories became the entire focus of painting compositions. Similarly, decorative works such aslacquerware containers, kimonos, and ceramic vessels are frequently ornamented in this way. When natural elements are employed as decorative motifs, they are frequently stylized to heighten the ornamental effect. Once again, these visual scenes often have literary references, heightening the image’s mood and cultural meaning.

| Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of ArtResource: Here |

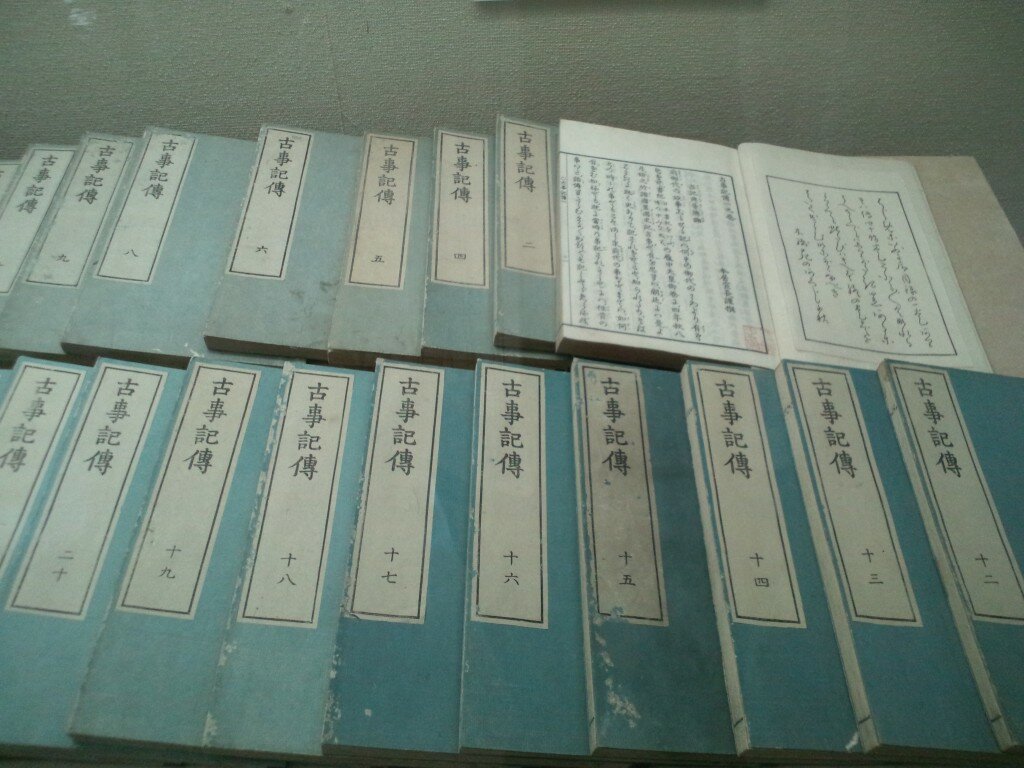

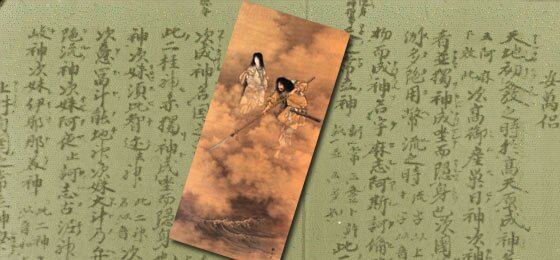

Kojiki

The Kojiki is one of the two primary sources for Shinto, the Japanese national religion. It starts in the realm of myth, with the creation of Japan from foam. Innumerable gods and goddesses are described. The narrative moves from mythology to historical legends, and culminates in a chronology of the early Imperial line.

The book is densely footnoted, almost to the point where the text is buried in apparatus. However, even this cannot shroud the wonderful story-telling. There are supernatural episodes, and tales of murder, passion and betrayal, all interspersed with extemporaneous poetry, reminiscent of Icelandic sagas.

Production notes: I worked on this for four years, on and off. I searched for a long time to locate a copy of the Tuttle reprint of the Chamberlain translation, which, despite being published in the 1970s is out of print and hard to obtain. In 2000, a copy fortuitously turned up in a local used bookstore. However, limitations of OCR technology at the time made it difficult to proof the text, so I put it aside. In 2005, I rescanned the book using more recent OCR software with better results, and managed to complete the proof. Even still, it took quite a bit of work to finish the job, particularly creating bitmaps of hundreds of images of Chinese and Japanese characters.

INTRODUCTION.

Of all the mass of Japanese literature, which lies before us as the result of nearly twelve centuries of book-making, the most important Monument is the work entitled “Ko-ji-ki” 1 or “Records of Ancient Matters,” which was completed in A. D. 712. It is the most important because it has preserved for us more faithfully than any other book the mythology, the manners, the language,

[paragraph continues] [2] and the traditional history of Ancient Japan. Indeed it is the earliest authentic connected literary product of that large division of the human race which, has been variously denominated Turanian, Scythian and Altaic, and it even precedes by at least a century the most ancient extant literary compositions of non-Aryan India. Soon after the date of its compilation, most of the salient features of distinctive Japanese nationality were buried under a superincumbent mass of Chinese culture, and it is to these “Records” and to a very small number of other ancient works, such as the poems of the “Collection of a Myriad Leaves” and the Shintō Rituals, that the investigator must look, if he would not at every step be misled in attributing originality to modern customs and ideas, which have simply been borrowed wholesale from the neighbouring continent.

It is of course not pretended that even these “Records” are untouched by Chinese influence: that influence is patent in the very characters with which the text is written. But the influence is less, and of another kind. If in the traditions preserved and in the customs alluded to we detect the Early Japanese in the act of borrowing from China and perhaps even from India, there is at least on our author’s part no ostentatious decking out in Chinese trappings of what he believed to be original matter, after the fashion of the writers who immediately succeeded him. It is true that this abstinence on his part makes his compilation less pleasant to the ordinary native taste than that of subsequent historians, who put fine Chinese phrases into the mouths of emperors and heroes supposed to have lived before the time when .intercourse with China began. But the European student,

who reads all such books, not as a pastime but in order to search for facts, will prefer the more genuine composition. It is also accorded the first place by the most learned of the native literati.

Of late years this paramount importance of the “Records of Ancient Matters” to investigators of Japanese subjects generally has become well-known to European scholars; and even versions of a few passages are to be found scattered through the pages of their writings. Thus Mr. Aston has given us, in the Chrestomathy appended to his “Grammar of the Japanese Written Language,” a couple of interesting extracts; Mr. Satow has illustrated by occasional extracts his elaborate papers on the Shintō Rituals printed in these “Transactions,” and a remarkable essay by Mr. Kempermann published in the Fourth [3] Number of the “Mittheilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Natur und Völkerkunde Ostasiens,” though containing no actual translations, bases on the account given in the “Records” some conjectures regarding the origines of Japanese civilization which are fully substantiated by more minute research. All that has yet appeared in any European language does not, however, amount to one-twentieth part of the whole, and the most erroneous views of the style and scope of the book and its contents have found their way into popular works on Japan. It is hoped that the true nature of the book, and also the true nature of the traditions, customs, and ideas of the Early Japanese, will be made clearer by the present translation the object of which is to give the entire work in a continuous English version, and thus to furnish the European student with a text to quote from, or at least to use as a guide in consulting the original. The only object aimed

at has been a rigid and literal conformity with the Japanese text. Fortunately for this endeavour (though less fortunately for the student), one of the difficulties which often beset the translator of an Oriental classic is absent in the present case. There is no beauty of style, to preserve some trace of which he may be tempted to sacrifice a certain amount of accuracy. The “Records” sound queer and bald in Japanese, as will be noticed further on, and it is therefore right, even from a stylistic point of view, that they should sound bald and queer in English. The only portions of the text which, from obvious reasons, refuse to lend themselves to translation into English after this fashion are the indecent portions. But it has been thought that there could be no objection to rendering them into Latin,—Latin as rigidly literal as is the English of the greater part.

After these preliminary remarks, it will be most convenient to take the several points which a study of the “Records” and the turning of them into English suggest, and to consider the same one by one. These points are:

II.—Details concerning the Method of Translation.

III.—The “Nihon-Gi” or “Chronicles of Japan”

IV.—Manners and Customs of the Early Japanese.

[4] V.—Religious and Political Ideas of the Early Japanese.

Beginnings of the Japanese Nation, and Credibility of the National Traditions.

for more information please click the link below:

By watching “47 Ronin” movie a few days a go I decided to put the real story in my blog:

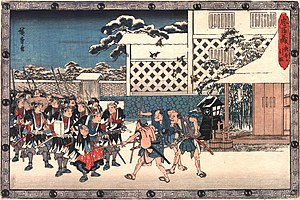

Forty-seven Ronin

Graves of the Forty-seven Ronin at Sengaku-ji

The revenge of the Forty-seven Ronin (四十七士 Shi-jū-shichi-shi?, forty-seven samurai) took place in Japan at the start of the 18th century. One noted Japanese scholar described the tale, the most famous example of the samurai code of honor, bushidō, as the country’s “national legend.”[1]

The story tells of a group of samurai who were left leaderless (becoming ronin) after their daimyo (feudal lord) Asano Naganori was compelled to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) for assaulting a court official named Kira Yoshinaka, whose title was Kōzuke no suke. The ronin avenged their master’s honor by killing Kira, after waiting and planning for almost two years. In turn, the ronin were themselves obliged to commit seppuku for committing the crime of murder. With much embellishment, this true story was popularized in Japanese culture as emblematic of the loyalty, sacrifice, persistence, and honor that people should preserve in their daily lives. The popularity of the tale grew during the Meiji era of Japanese history, in which Japan underwent rapid modernization, and the legend became subsumed within discourses of national heritage and identity.

Fictionalized accounts of the tale of the Forty-seven Ronin are known as Chūshingura. The story was popularized in numerous plays, including bunraku and kabuki. Because of the censorship laws of the shogunate in the Genroku era, which forbade portrayal of current events, the names were changed. While the version given by the playwrights may have come to be accepted as historical fact by some, the first Chūshingura was written some 50 years after the event, and numerous historical records about the actual events that predate the Chūshingura survive.

The bakufu‘s censorship laws had relaxed somewhat 75 years later in the late 18th century, when Japanologist Isaac Titsingh first recorded the story of the Forty-seven Ronin as one of the significant events of the Genroku era.[2] The story continues to be popular in Japan to this day. Each year on December 14, Sengakuji Temple holds a festival commemorating the event.

Name

The participants in the revenge are called the Shi-jū-shichi-shi (四十七士?) in Japanese, and are usually referred to as the “Forty-seven Ronin” or “Forty-seven lordless samurai” in English. The event is also known as the Akō vendetta or the Genroku Akō incident (元禄赤穂事件 Genroku akō jiken?). Literary accounts of the events are known as theChūshingura (忠臣蔵 The Treasury of Loyal Retainers?).

Story

In 1701 (by the Western calendar), two daimyo, Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori, the young daimyo of the Akō Domain (a small fiefdom in western Honshū), and Lord Kamei of theTsuwano Domain, were ordered to arrange a fitting reception for the envoys of the Emperor in Edo, during their sankin kōtai service to the Shogun.[3]

These daimyo names are not fictional, nor is there any question that something actually happened in Genroku (year) 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month (元禄十五年十二月十四日?, Tuesday, January 30, 1703).[4] What is commonly called the Akō incident was an actual event.[2]

For many years, the version of events retold by A. B. Mitford in Tales of Old Japan (1871) was considered authoritative. The sequence of events and the characters in this narrative were presented to a wide popular readership in the West. Mitford invited his readers to construe his story of the Forty-seven Ronin as historically accurate; and while his version of the tale has long been considered a standard work, some of its precise details are now questioned.[5] Nevertheless, even with plausible defects, Mitford’s work remains a conventional starting point for further study.[5]

Whether as a mere literary device or as a claim for ethnographic veracity, Mitford explains:

In the midst of a nest of venerable trees in Takanawa, a suburb of Yedo, is hidden Sengakuji, or the Spring-hill Temple, renowned throughout the length and breadth of the land for its cemetery, which contains the graves of the Forty-seven Rônin, famous in Japanese history, heroes of Japanese drama, the tale of whose deed I am about to transcribe.

— Mitford, A. B.[6] [emphasis added]

Mitford appended what he explained were translations of Sengakuji documents the author had examined personally. These were proffered as “proofs” authenticating the factual basis of his story.[7] These documents were:

- …the receipt given by the retainers of Kira Kôtsuké no Suké’s son in return for the head of their lord’s father, which the priests restored to the family.[8]

- …a document explanatory of their conduct, a copy of which was found on the person of each of the forty-seven men, dated in the 15th year of Genroku, 12th month.[9]

- …a paper which the Forty-seven Rǒnin laid upon the tomb of their master, together with the head of Kira Kôtsuké no Suké.[10]

(See Tales of Old Japan for the widely known, yet significantly fictional narrative.)

Genesis of a tragedy

Ukiyo-e depicting Asano Naganori’s assault on Kira Yoshinaka in the Matsu no Ōrōka of Edo Castle

Memorial stone marking the site of theMatsu no Ōrōka (Great Corridor of Pines) inEdo Castle, where Asano attacked Kira

Asano and Kamei were to be given instruction in the necessary court etiquette by Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful Edo official in the hierarchy of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi‘s shogunate. He became upset at them, allegedly either because of the insufficient presents they offered him (in the time-honored compensation for such an instructor), or because they would not offer bribes as he wanted. Other sources say that he was naturally rude and arrogant, or that he was corrupt, which offended Asano, a devoutly moral Confucian. Whether Kira treated them poorly, insulted them, or failed to prepare them for fulfilling specific bakufu duties,[11] offense was taken.[2]

While Asano bore all this stoically, Kamei became enraged and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, the quick thinking counsellors of Kamei averted disaster for their lord and clan (for all would have been punished if Kamei had killed Kira) by quietly giving Kira a large bribe; Kira thereupon began to treat Kamei nicely, which calmed Kamei.[12]

However, Kira allegedly continued to treat Asano harshly, because he was upset that the latter had not emulated his companion. Finally, Kira insulted Asano, calling him a country boor with no manners, and Asano could restrain himself no longer. At the Matsu no Ōrōka, the main grand corridor that interconnects different parts of the shogun’s residence, Asano lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, wounding him in the face with his first strike; his second missed and hit a pillar. Guards then quickly separated them.[13]

Kira’s wound was hardly serious, but the attack on a shogunate official within the boundaries of the shogun’s residence was considered a grave offense. Any kind of violence, even drawing a katana, was completely forbidden in Edo Castle.[14] The daimyo of Akō had removed his dagger from its scabbard within Edo Castle, and for that offense, he was ordered to kill himself by committingseppuku.[2] Asano’s goods and lands were to be confiscated after his death, his family was to be ruined, and his retainers were to be made ronin (leaderless).

This news was carried to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano’s principal counsellor, who took command and moved the Asano family away, before complying with bakufu orders to surrender the castle to the agents of the government.

The ronin plot revenge

Two of the Forty-Seven Ronin: Horibe Yahei and his adopted son, Horibe Yasubei. Yasubei is holding an ōtsuchi.

Of Asano’s over three hundred men, forty-seven (some sources say there were originally more than fifty)—and especially their leader Ōishi—refused to allow their lord to go unavenged, even though revenge had been prohibited in the case. They banded together, swearing a secret oath to avenge their master by killing Kira, even though they knew they would be severely punished for doing so.

Kira was well guarded, however, and his residence had been fortified to prevent just such an event. The ronin saw that they would have to put him off his guard before they could succeed. To quell the suspicions of Kira and other shogunate authorities, they dispersed and became tradesmen and monks.

Ōishi took up residence in Kyoto and began to frequently visit brothels and taverns, as if nothing were further from his mind than revenge. Kira still feared a trap, and sent spies to watch the former retainers of Asano.

One day, as Ōishi returned home drunk, he fell down in the street and went to sleep, and all the passers-by laughed at him. ASatsuma man, passing by, was infuriated by this behaviour on the part of a samurai—by his lack of courage to avenge his master as well as his current debauched behaviour. The Satsuma man abused and insulted Ōishi, kicked him in the face (to even touch the face of a samurai was a great insult, let alone strike it), and spat on him.

Not too long after, Ōishi went to his loyal wife of twenty years and divorced her so that no harm would come to her when the ronin took revenge. He sent her away with their two younger children to live with her parents; he gave the eldest boy, Chikara, a choice to stay and fight or to leave. Chikara remained with his father.

Ōishi began to act oddly and very unlike the composed samurai. He frequented geisha houses (particularly Ichiriki Chaya), drank nightly, and acted obscenely in public. Ōishi’s men bought a geisha, hoping she would calm him. This was all a ruse to rid Ōishi of his spies.

Kira’s agents reported all this to Kira, who became convinced that he was safe from the retainers of Asano, that they must all be bad samurai indeed, without the courage to avenge their master after a year and a half. Thinking them harmless and lacking funds from his “retirement”, he then reluctantly let down his guard.

The rest of the faithful ronin now gathered in Edo, and in their roles as workmen and merchants gained access to Kira’s house, becoming familiar with the layout of the house and the character of all within. One of the retainers (Kinemon Kanehide Okano) went so far as to marry the daughter of the builder of the house, to obtain the house’s design plans. All of this was reported to Ōishi. Others gathered arms and secretly transported them to Edo, another offense.

The attack

After two years, when Ōishi was convinced that Kira was thoroughly off his guard,[15] and everything was ready, he fled from Kyoto, avoiding the spies who were watching him, and the entire band gathered at a secret meeting place in Edo to renew their oaths.

In Genroku 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month (元禄十五年十二月十四日?, Tuesday, January 30, 1703),[4] early in the morning in a driving wind during a heavy fall of snow, Ōishi and the ronin attacked Kira Yoshinaka’s mansion in Edo. According to a carefully laid-out plan, they split up into two groups and attacked, armed with swords and bows. One group, led by Ōishi, was to attack the front gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, was to attack the house via the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal that Kira was dead.[16]

Once Kira was dead, they planned to cut off his head and lay it as an offering on their master’s tomb. They would then turn themselves in and wait for their expected sentence of death.[17] All this had been confirmed at a final dinner, at which Ōishi had asked them to be careful and spare women, children, and other helpless people.[18] (The code of bushido does not require mercy to noncombatants, nor forbids it.)

Ōishi had four men scale the fence and enter the porter’s lodge, capturing and tying up the guard there.[19] He then sent messengers to all the neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but retainers out to avenge the death of their master, and that no harm would come to anyone else: the neighbors were all safe. One of the ronin climbed to the roof and loudly announced to the neighbors that the matter was a revenge act (katakiuchi, 敵討ち). The neighbors, who all hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to hinder the raiders.[20]

After posting archers (some on the roof) to prevent those in the house (who had not yet awakened) from sending for help, Ōishi sounded the drum to start the attack. Ten of Kira’s retainers held off the party attacking the house from the front, but Ōishi Chikara’s party broke into the back of the house.[21]

Kira, in terror, took refuge in a closet in the veranda, along with his wife and female servants. The rest of his retainers, who slept in barracks outside, attempted to come into the house to his rescue. After overcoming the defenders at the front of the house, the two parties led by father and son joined up and fought the retainers who came in. The latter, perceiving that they were losing, tried to send for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers posted to prevent that eventuality.[22]

Eventually, after a fierce struggle, the last of Kira’s retainers was subdued; in the process the ronin killed sixteen of Kira’s men and wounded twenty-two, including his grandson. Of Kira, however, there was no sign. They searched the house, but all they found were crying women and children. They began to despair, but Ōishi checked Kira’s bed, and it was still warm, so he knew he could not be far away.[23]

The death of Kira

A renewed search disclosed an entrance to a secret courtyard hidden behind a large scroll; the courtyard held a small building for storing charcoal and firewood, where two more hidden armed retainers were overcome and killed. A search of the building disclosed a man hiding; he attacked the searcher with a dagger, but the man was easily disarmed.[24]

He refused to say who he was, but the searchers felt sure it was Kira, and sounded the whistle. The ronin gathered, and Ōishi, with a lantern, saw that it was indeed Kira—as a final proof, his head bore the scar from Asano’s attack.[25]

At that, Ōishi went on his knees, and in consideration of Kira’s high rank, respectfully addressed him, telling him they were retainers of Asano, come to avenge him as true samurai should, and inviting Kira to die as a true samurai should, by killing himself. Ōishi indicated he personally would act as a kaishakunin (“second”, the one who beheads a person committing harakiri to spare them the indignity of a lingering death) and offered him the same dagger that Asano had used to kill himself.[26]

However, no matter how much they entreated him, Kira crouched, speechless, and trembling. At last, seeing it was useless to ask, Ōishi ordered the other ronin to pin him down, and killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger. Kira was killed on the night of the 14th day of the 12th month of the 15th year of Genroku (1703-01-30 Gregorian[27]).

They then extinguished all the lamps and fires in the house (lest any cause the house to catch fire and start a general fire that would harm the neighbors) and left, taking Kira’s head.[28]

One of the ronin, the ashigaru Terasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to travel to Akō and report that their revenge had been completed. (Though Kichiemon’s role as a messenger is the most widely accepted version of the story, other accounts have him running away before or after the battle, or being ordered to leave before the ronin turned themselves in.)[29]

The aftermath

As day was now breaking, they quickly carried Kira’s head from his residence to their lord’s grave in Sengaku-ji temple, marching about ten kilometers across the city, causing a great stir on the way. The story of the revenge spread quickly, and everyone on their path praised them and offered them refreshment.[30]

On arriving at the temple, the remaining forty-six ronin (all except Terasaka Kichiemon) washed and cleaned Kira’s head in a well, and laid it, and the fateful dagger, before Asano’s tomb. They then offered prayers at the temple, and gave the abbot of the temple all the money they had left, asking him to bury them decently, and offer prayers for them. They then turned themselves in; the group was broken into four parts and put under guard of four different daimyo.[31]

During this time, two friends of Kira came to collect his head for burial; the temple still has the original receipt for the head, which the friends and the priests who dealt with them all signed.[8]

The shogunate officials in Edo were in a quandary. The samurai had followed the precepts of bushido by avenging the death of their lord; but they had also defied the shogunate authority by exacting revenge, which had been prohibited. In addition, the Shogun received a number of petitions from the admiring populace on behalf of the ronin. As expected, the ronin were sentenced to death for the murder of Kira; but the Shogun had finally resolved the quandary by ordering them to honorably commit seppuku instead of having them executed as criminals.[32] It is known that each of the assailants ended his life in a ritualistic fashion.[2] Ōishi Chikara, the youngest, was only 15 years old on the day the raid took place, and only 16 the day he had to commit seppuku.

Each of the forty-six ronin killed himself in Genroku 16, on the 4th day of the 2nd month (元禄十六年二月四日?, Tuesday, March 20, 1703).[4] This has caused a considerable amount of confusion ever since, with some people referring to the “forty-six ronin”; this refers to the group put to death by the Shogun, while the actual attack party numbered forty-seven. The forty-seventh ronin, identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was pardoned by the Shogun (some say on account of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying around 1747, and was then buried with his comrades. The assailants who died by seppuku were subsequently interred on the grounds of Sengaku-ji,[2] in front of the tomb of their master.[32]

The clothes and arms they wore are still preserved in the temple to this day, along with the drum and whistle; the armor was all home-made, as they had not wanted to arouse suspicion by purchasing any.

The tombs became a place of great veneration, and people flocked there to pray. The graves at the temple have been visited by a great many people throughout the years since the Genroku era.[2] One of those who visited the tombs was the Satsuma man who had mocked and spat on Ōishi as he lay drunk in the street. Addressing the grave, he begged for forgiveness for his actions and for thinking that Ōishi was not a true samurai. He then committed suicide and was buried next to the graves of the ronin.[32]

Re-establishment of the Asano clan’s lordship

Though the revenge is often viewed as an act of loyalty, there had been a second goal, to re-establish the Asanos’ lordship and finding a place for fellow samurai to serve. Hundreds of samurai who had served under Asano had been left jobless, and many were unable to find employment, as they had served under a disgraced family. Many lived as farmers or did simple handicrafts to make ends meet. The revenge of the Forty-seven Ronin cleared their names, and many of the unemployed samurai found jobs soon after the ronin had been sentenced to their honorable end.

Asano Daigaku Nagahiro, Naganori’s younger brother and heir, was allowed by the Tokugawa Shogunate to re-establish his name, though his territory was reduced to a tenth of the original.

Criticism

The ronin spent more than a year waiting for the “right time” for their revenge. It was Yamamoto Tsunetomo, author of the Hagakure, who asked this famous question: “What if, nine months after Asano’s death, Kira had died of an illness?” His answer was that the Forty-seven Ronin would have lost their only chance at avenging their master. Even if they had claimed, then, that their dissipated behavior was just an act, that in just a little more time they would have been ready for revenge, who would have believed them? They would have been forever remembered as cowards and drunkards—bringing eternal shame to the name of the Asano clan. The right thing for the ronin to do, wrote Yamamoto, according to proper bushido, was to attack Kira and his men immediately after Asano’s death. The ronin would probably have suffered defeat, as Kira was ready for an attack at that time—but this was unimportant.[33]

Ōishi, from the perspective of bushido, was too obsessed with success, according to Yamamoto. He conceived his convoluted plan to ensure they would succeed at killing Kira, which is not a proper concern in a samurai: the important thing was not the death of Kira, but for the former samurai of Asano to show outstanding courage and determination in an all-out attack against the Kira house, thus winning everlasting honor for their dead master. Even if they had failed to kill Kira, even if they had all perished, it would not have mattered, as victory and defeat have no importance in bushido. By waiting a year, they improved their chances of success but risked dishonoring the name of their clan, the worst sin a samurai can commit. This is why Yamamoto and others claim that the tale of the Forty-seven Ronin is a good story of revenge, but by no means a story of bushido.[33]

In the arts

The tragedy of the Forty-seven Ronin has been one of the most popular themes in Japanese art, and has lately even begun to make its way into Western art.

Immediately following the event, there were mixed feelings among the intelligentsia about whether such vengeance had been appropriate. Many agreed that, given their master’s last wishes, the ronin had done the right thing, but were undecided about whether such a vengeful wish was proper. Over time, however, the story became a symbol, not of bushido, as the ronin can be seen as seriously lacking it, but of loyalty to one’s master and later, of loyalty to the emperor. Once this happened, the story flourished as a subject of drama, storytelling, and visual art.

Plays

The incident immediately inspired a succession of kabuki and bunraku plays; the first, The Night Attack at Dawn by the Soga appeared only two weeks after the ronin died. It was shut down by the authorities, but many others soon followed, initially in Osaka and Kyoto, farther away from the capital. Some even took the story as far as Manila, to spread the story to the rest of Asia.

The most successful of the adaptations was a bunraku puppet play called Kanadehon Chūshingura (now simply called Chūshingura, or “Treasury of Loyal Retainers”), written in 1748 by Takeda Izumo and two associates; it was later adapted into a kabuki play, which is still one of Japan’s most popular.

In the play, to avoid the attention of the censors, the events are transferred into the distant past, to the 14th century reign of shogun Ashikaga Takauji. Asano became Enya Hangan Takasada, Kira became Ko no Moronao and Ōishi became Ōboshi Yuranosuke Yoshio; the names of the rest of the ronin were disguised to varying degrees. The play contains a number of plot twists that do not reflect the real story: Moronao tries to seduce Enya’s wife, and one of the ronin dies before the attack because of a conflict between family and warrior loyalty (another possible cause of the confusion between forty-six and forty-seven).

Opera

The story was turned into an opera, Chūshingura, by Shigeaki Saegusa in 1997.

Cinema and television

The play has been made into a movie at least six times in Japan,[34] the earliest starring Onoe Matsunosuke. The film’s release date is questioned, but placed between 1910 and 1917. It has been aired on the Jidaigeki Senmon Channel (Japan) with accompanying benshi narration. In 1941, the Japanese military commissioned director Kenji Mizoguchi, who would later direct Ugetsu, to make Genroku Chūshingura. They wanted a ferocious morale booster based upon the familiar rekishi geki (“historical drama”) of The Loyal 47 Ronin. Instead, Mizoguchi chose for his source Mayama Chūshingura, a cerebral play dealing with the story. The film was a commercial failure, having been released in Japan one week before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese military and most audiences found the first part to be too serious, but the studio and Mizoguchi both regarded it as so important that Part Two was put into production, despite Part One’s lukewarm reception. Renowned by postwar scholars lucky to have seen it in Japan, the film wasn’t shown in America until the 1970s.[35]

The 1962 film version directed by Hiroshi Inagaki, Chūshingura, is most familiar to Western audiences.[34] In it, Toshiro Mifune appears in a supporting role as spearman Tawaraboshi Genba. Mifune was to revisit the story several times in his career. In 1971 he appeared in the 52-part television series Daichūshingura as Ōishi, while in 1978 he appeared as Lord Tsuchiya in the epic Swords of Vengeance (Ako-Jo danzetsu).

Many Japanese television shows, including single programs, short series, single seasons, and even year-long series such as Daichūshingura and the more recent NHK Taiga drama Genroku Ryōran, recount the events of the Forty-seven Ronin. Among both films and television programs, some are quite faithful to the Chūshingura, while others incorporate unrelated material or alter details. In addition, gaiden dramatize events and characters not in the Chūshingura. Kon Ichikawa directed another version in 1994. In 2004, Saito Mitsumasa directed a 9-episode mini-series starring Matsudaira Ken, who also starred in a 1999 49-episode TV series of the Chūshingura entitled Genroku Ryoran. In Hirokazu Koreeda‘s 2006 film Hana yori mo naho, the events of the Forty-seven Ronin story was used as a backdrop, one of the ronin being a neighbour of the protagonists.

Woodblock prints

The Forty-seven Ronin are one of the most popular themes in woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e and many well-known artists have made prints portraying either the original events, scenes from the play, or the actors. One book on subjects depicted in woodblock prints devotes no fewer than seven chapters to the history of the appearance of this theme in woodblocks. Among the artists who produced prints on this subject are Utamaro, Toyokuni, Hokusai, Kunisada, Hiroshige, and Yoshitoshi.[36] However, probably the most famous woodblocks in the genre are those of Kuniyoshi, who produced at least eleven separate complete series on this subject, along with more than twenty triptychs.

In the West

- The earliest known account of the Akō incident in the West was published in 1822 in Isaac Titsingh‘s posthumously-published book Illustrations of Japan.[2]

- The action film 47 Ronin was released on December 25, 2013, by Universal Pictures and starred Keanu Reeves as an outcast who joins the samurai in their quest to avenge their slain master. Some of the most famous current Japanese actors, such as Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, Kō Shibasaki, Rinko Kikuchi, and Jin Akanishi, appear in the film.

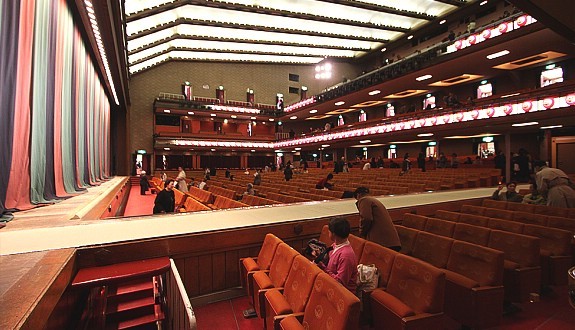

Kabuki

Kanamaruza Theater, a traditional kabuki theaterKabuki (歌舞伎) is a traditional Japanese form of theater with roots tracing back to the Edo Period. It is recognized as one of Japan’s three major classical theaters along with noh and bunraku, and has been named as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Kanamaruza Theater, a traditional kabuki theaterKabuki (歌舞伎) is a traditional Japanese form of theater with roots tracing back to the Edo Period. It is recognized as one of Japan’s three major classical theaters along with noh and bunraku, and has been named as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

What is it?

Kabuki is an art form rich in showmanship. It involves elaborately designed costumes, eye-catching make-up, outlandish wigs, and arguably most importantly, the exaggerated actions performed by the actors. The highly-stylized movements serve to convey meaning to the audience; this is especially important since an old-fashioned form of Japanese is typically used, which is difficult even for Japanese people to fully understand.

Dynamic stage sets such as revolving platforms and trapdoors allow for the prompt changing of a scene or the appearance/disappearance of actors. Another specialty of the kabuki stage is a footbridge (hanamichi) that leads through the audience, allowing for a dramatic entrance or exit. Ambiance is aided with live music performed usingtraditional instruments. These elements combine to produce a visually stunning and captivating performance.

Plots are usually based on historical events, warm hearted dramas, moral conflicts, love stories, tales of tragedy of conspiracy, or other well-known stories. A unique feature of a kabuki performance is that what is on show is often only part of an entire story (usually the best part). Therefore, to enhance the enjoyment derived, it would be good to read a little about the story before attending the show. At some theaters, it is possible to rent headsets which provide English narrations and explanations.

The interior of the previous Kabukiza Theater, a modern kabuki theaterKabuki conventions

The interior of the previous Kabukiza Theater, a modern kabuki theaterKabuki conventions

When it originated, kabuki used to be acted only by women, and was popular mainly among common people. Later during the Edo Period, a restriction was placed by the Tokugawa Shogunate forbidding women from participating; to the present day it is performed exclusively by men. Several male kabuki actors are therefore specialists in playing female roles (onnagata).

One of the things that will be noticed are assistants dressed in black appearing on stage. They serve the purpose to hand the actors props or assist them in various other ways, in order to make the performance seamless. They are called “kurogo” and are to be regarded as non-existent.

If you come across people from the audience shouting out names at the actors on stage, do not mistake this for an act of disrespect: all kabuki actors have a yago (hereditary stage name), which is closely associated to the theater troupe which he is from. In the world of kabuki, troupes are closely knit hierarchical organizations, usually continued through generations within families. It is an accepted practice for the audience to shout out the actors’ stage names at an appropriate timing as a show of support.

Formal dress code is not required when attending a kabuki play, although decent dressing and footwear are recommended. Sometimes, often on the first day of a run, some ladies dress in traditional kimono.

Rotating stage of a traditional kabuki theater from belowWhere to watch it

Rotating stage of a traditional kabuki theater from belowWhere to watch it

In the olden days, mainstream kabuki was performed at selected venues in big cities like Edo (present dayTokyo), Osaka and Kyoto. Local versions of kabuki also took place in rural towns.

These days, kabuki plays are most easily enjoyed at selected theaters with Western style seats. A day’s performance is usually divided into two or three segments (one in the early afternoon and one towards the evening), and each segment is further divided into acts. Tickets are usually sold per segment, although in some cases they are also available per act. They typically cost around 2,000 yen for a single act or between 3,000 and 25,000 yen for an entire segment depending on the seat quality.

| reference: Japan guide |

GoodReads

GoodReads