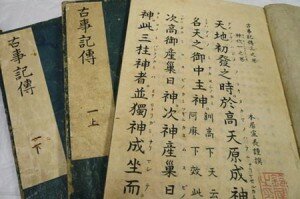

Japanese Creation Myth (712 CE)

From Genji Shibukawa: Tales from the Kojiki

The following is a modern retelling of the creation story from the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest chronicle, compiled in 712 CE by O No Yasumaro. This version is easier for the modern reader to understand than the original, but its essential features are preserved. The quest for Izanami in the underworld is reminiscent of the Greek demigod Orpheus’ quest in Hades for his wife, Euridice, and even more of the Sumerian myth of the descent of Innana to the underworld.

How does this story reflect the sense of its creators that Japan is the most important place in the world?

The Beginning of the World

Before the heavens and the earth came into existence, all was a chaos, unimaginably limitless and without definite shape or form. Eon followed eon: then, lo! out of this boundless, shapeless mass something light and transparent rose up and formed the heaven. This was the Plain of High Heaven, in which materialized a deity called Ame-no-Minaka-Nushi-no-Mikoto (the Deity-of-the-August-Center-of-Heaven). Next the heavens gave birth to a deity named Takami-Musubi-no-Mikoto (the High-August-Producing-Wondrous-Deity), followed by a third called Kammi-Musubi-no-Mikoto (the Divine-Producing-Wondrous-Deity). These three divine beings are called the Three Creating Deities.

In the meantime what was heavy and opaque in the void gradually precipitated and became the earth, but it had taken an immeasurably long time before it condensed sufficiently to form solid ground. In its earliest stages, for millions and millions of years, the earth may be said to have resembled oil floating, medusa-like, upon the face of the waters. Suddenly like the sprouting up of a reed, a pair of immortals were born from its bosom. These were the Deity Umashi-Ashi-Kahibi-Hikoji-no-Mikoto (the Pleasant-Reed-Shoot-Prince-Elder-Deity) and the Deity Ame-no-Tokotachi-no-Mikoto (The Heavenly-Eternally-Standing-Deity). . . .

Many gods were thus born in succession, and so they increased in number, but as long as the world remained in a chaotic state, there was nothing for them to do. Whereupon, all the Heavenly deities summoned the two divine beings, Izanagi and Izanami, and bade them descend to the nebulous place, and by helping each other, to consolidate it into terra firma. “We bestow on you,” they said, “this precious treasure, with which to rule the land, the creation of which we command you to perform.” So saying they handed them a spear called Ama-no-Nuboko, embellished with costly gems. The divine couple received respectfully and ceremoniously the sacred weapon and then withdrew from the presence of the Deities, ready to perform their august commission. Proceeding forthwith to the Floating Bridge of Heaven, which lay between the heaven and the earth, they stood awhile to gaze on that which lay below. What they beheld was a world not yet condensed, but looking like a sea of filmy fog floating to and fro in the air, exhaling the while an inexpressibly fragrant odor. They were, at first, perplexed just how and where to start, but at length Izanagi suggested to his companion that they should try the effect of stirring up the brine with their spear. So saying he pushed down the jeweled shaft and found that it touched something. Then drawing it up, he examined it and observed that the great drops which fell from it almost immediately coagulated into an island, which is, to this day, the Island of Onokoro. Delighted at the result, the two deities descended forthwith from the Floating Bridge to reach the miraculously created island. In this island they thenceforth dwelt and made it the basis of their subsequent task of creating a country. Then wishing to become espoused, they erected in the center oPound the island a pillar, the Heavenly August Pillar, and built around it a great palace called the Hall of Eight Fathoms. Thereupon the male Deity turning to the left and the female Deity to the right, each went round the pillar in opposite directions. When they again met each other on the further side of the pillar, Izanami, the female Deity, speaking first, exclaimed: “How delightful it is to meet so handsome a youth!” To which Izanagi, the male Deity, replied: “How delightful I am to have fallen in with such a lovely maiden!” After having spoken thus, the male Deity said that it was not in order that woman should anticipate man in a greeting. Nevertheless, they fell into connubial relationship, having been instructed by two wagtails which flew to the spot. Presently the Goddess bore her divine consort a son, but the baby was weak and boneless as a leech. Disgusted with it, they abandoned it on the waters, putting it in a boat made of reeds. Their second offspring was as disappointing as the first. The two Deities, now sorely disappointed at their failure and full of misgivings, ascended to Heaven to inquire of the Heavenly Deities the causes of their misfortunes. The latter performed the ceremony of divining and said to them: “It is the woman’s fault. In turning round the Pillar, it was not right and proper that the female Deity should in speaking have taken precedence of the male. That is the reason.” The two Deities saw the truth of this divine suggestion, and made up their minds to rectify the error. So, returning to the earth again, they went once more around the Heavenly Pillar. This time Izanagi spoke first saying: “How delightful to meet so beautiful a maiden!” “How happy I am,” responded Izanami, “that I should meet such a handsom youth!” This process was more appropriate and in accordance with the law of nature. After this, all the children born to them left nothing to be desired. First, the island of Awaji was born, next, Shikoku, then, the island of Oki, followed by Kyushu; after that, the island Tsushima came into being, and lastly, Honshu, the main island of Japan. The name of Oyashi- ma-kuni (the Country of the Eight Great Islands) was given to these eight islands. After this, the two Deities became the parents of numerous smaller islands destined to surround the larger ones.

The Birth of the Deities

Having, thus, made a country from what had formerly been no more than a mere floating mass, the two Deities, Izanagi and Izanami, about begetting those deities destined to preside over the land, sea, mountains, rivers, trees, and herbs. Their first-born proved to be the sea-god, Owatatsumi-no-Kami. Next they gave birth to the patron gods of harbors, the male deity Kamihaya-akitsu-hiko having control of the land and the goddess Haya-akitsu-hime having control of the sea. These two latter deities subsequently gave birth to eight other gods.

Next Izanagi and Izanami gave birth to the wind-deity, Kami-Shinatsuhiko-no-Mikoto. At the moment of his birth, his breath was so potent that the clouds and mists, which had hung over the earth from the beginning of time, were immediately dispersed. In consequence, every corner of the world was filled with brightness. Kukunochi-no-Kami, the deity of trees, was the next to be born, followed by Oyamatsumi-no-Kami, the deity of mountains, and Kayanuhime-no-Kami, the goddess of the plains. . . .

The process of procreation had, so far, gone on happily, but at the birth of Kagutsuchi-no-Kami, the deity of fire, an unseen misfortune befell the divine mother, Izanami. During the course of her confinement, the goddess was so severely burned by the flaming child that she swooned away. Her divine consort, deeply alarmed, did all in his power to resuscitate her, but although he succeeded in restoring her to consciousness, her appetite had completely gone. Izanagi, thereupon and with the utmost loving care, prepared for her delectation various tasty dishes, but all to no avail, because whatever she swallowed was almost immediately rejected. It was in this wise that occurred the greatest miracle of all. From her mouth sprang Kanayama- biko and Kanayama-hime, respectively the god and goddess of metals, whilst from other parts of her body issued forth Haniyasu-hiko and Haniyasu-hime, respectively the god and goddess of earth. Before making her “divine retirement,” which marks the end of her earthly career, in a manner almost unspeakably miraculous she gave birth to her last-born, the goddess Mizuhame-no-Mikoto. Her demise marks the intrusion of death into the world. Similarly the corruption of her body and the grief occasioned by her death were each the first of their kind.

By the death of his faithful spouse Izanagi was now quite alone in the world. In conjunction with her, and in accordance with the instructions of the Heavenly Gods, he had created and consolidated the Island Empire of Japan. In the fulfillment of their divine mission, he and his heavenly spouse had lived an ideal life of mutual love and cooperation. It is only natural, therefore, that her death should have dealt him a truly mortal blow.

He threw himself upon her prostrate form, crying: “Oh, my dearest wife, why art thou gone, to leave me thus alone? How could I ever exchange thee for even one child? Come back for the sake of the world, in which there still remains so much for both us twain to do.” In a fit of uncontrollable grief, he stood sobbing at the head of the bier. His hot tears fell like hailstones, and lo! out of the tear-drops was born a beauteous babe, the goddess Nakisawame-no-Mikoto. In deep astonishment he stayed his tears, a gazed in wonder at the new-born child, but soon his tears returned only to fall faster than before. It was thus that a sudden change came over his state of mind. With bitter wrath, his eyes fell upon the infant god of fire, whose birth had proved so fatal to his mother. He drew his sword, Totsuka-no-tsurugi, and crying in his wrath, “Thou hateful matricide,” decapitated his fiery offspring. Up shot a crimson spout of blood. Out of the sword and blood together arose eight strong and gallant deities. “What! more children?” cried Izanagi, much astounded at their sudden appearance, but the very next moment, what should he see but eight more deities born from the lifeless body of the infant firegod! They came out from the various parts of the body,–head, breast, stomach, hands, feet, and navel, and, to add to his astonishment, all of them were glaring fiercely at him. Altogether stupefied he surveyed the new arrivals one after another.

Meanwhile Izanami, for whom her divine husband pined so bitterly, had quitted this world for good and all and gone to the Land of Hades.

Izanagi’s Visit to the Land of Hades

As for the Deity Izanagi, who had now become a widower, the presence of so many offspring might have, to some extent, beguiled and solaced him, and yet when he remembered how faithful his departed spouse had been to him, he would yearn for her again, his heart swollen with sorrow and his eyes filled with tears. In this mood, sitting up alone at midnight, he would call her name aloud again and again, regardless of the fact that he could hope for no response. His own piteous cries merely echoed back from the walls of his chamber.

Unable any longer to bear his grief, he resolved to go down to the Nether Regions in order to seek for Izanami and bring her back, at all costs, to the world. He started on his long and dubious journey. Many millions of miles separated the earth from the Lower Regions and there were countless steep and dangerous places to be negotiated, but Izanagi’s indomitable determination to recover his wife enabled him finally to overcome all these difficulties. At length he succeeded in arriving at his destination. Far ahead of him, he espied a large castle. “That, no doubt,” he mused in delight, “may be where she resides.”

Summoning up all his courage, he approached the main entrance of the castle. Here he saw a number of gigantic demons, some red some black, guarding the gates with watchful eyes. He retraced his steps in alarm, and stole round to a gate at the rear of the castle. He found, to his great joy, that it was apparently left unwatched. He crept warily through the gate and peered into the interior of the castle, when he immediately caught sight of his wife standing at the gate at an inner court. The delighted Deity loudly called her name. “Why! There is some one calling me,” sighed Izanami-no-Mikoto, and raising her beautiful head, she looked around her. What was her amazement but to see her beloved husband standing by the gate and gazing at her intently! He had, in fact, been in her thoughts no less constantly than she in his. With a heart leaping with joy, she approached him. He grasped her hands tenderly and murmured in deep and earnest tones: “My darling, I have come to take thee back to the world. Come back, I pray thee, and let us complete our work of creation in accordance with the will of the Heavenly Gods,–our work which was left only half accomplished by thy departure. How can I do this work without thee?Thy loss means to me the loss of all.” This appeal came from the depth of his heart. The goddess sympathized with him most deeply, but answered with tender grief: “Alas! Thou hast come too late. I have already eaten of the furnace of Hades. Having once eaten the things of this land, it is impossible for me to come back to the world.” So saying, she lowered her head in deep despair.

“Nay, I must entreat thee to come back. Canst not thou find some means by which this can be accomplished?” exclaimed her husband, drawing nearer to her. After some reflection, she replied: “Thou hast come a very, very long way for my sake. How much I appreciate thy devotion! I wish, with all my heart, to go back with thee, but before I can do so, I must first obtain the permission of the deities of Hades. Wait here till my return, but remember that thou must not on any account look inside the castle in the meantime. ” I swear I will do as thou biddest,” quoth Izanagi, ” but tarry not in thy quest.” With implicit confidence in her husband’s pledge, the goddess disappeared into the castle.

Izanagi observed strictly her injunction. He remained where he stood, and waited impatiently for his wife’s return. Probably to his impatient mind, a single heart-beat may have seemed an age. He waited and waited, but no shadow of his wife appeared. The day gradually wore on and waned away, darkness was about to fall, and a strange unearthly wind began to strike his face. Brave as he was, he was seized with an uncanny feeling of apprehension. Forgetting the vow he had made to the goddess, he broke off one of the teeth of the comb which he was wearing in the left bunch of his hair, and having lighted it, he crept in softly and- glanced around him. To his horror he found Izanagi lying dead in a room: and lo! a ghastly change had come over her. She, who had been so dazzlingly beautiful, was now become naught but a rotting corpse, in an advanced stage of decomposition. Now, an even more horrible sight met his gaze; the Fire Thunder dwelt in her, head, the Black Thunder in her belly, the Rending-Thunder in her abdomen, the Young Thunder in her left hand, the Earth-Thunder in her right hand, the Rumbling-Thunder in her left foot,-and the Couchant Thunder in her right foot:–altogether eight Thunder-Deities had been born and were dwelling there, attached to her remains and belching forth flames from their mouths. Izanagitno-Mikoto was so thoroughly alarmed at the sight, that he dropped the light and took to his heels. The sound he made awakened Izanami from her death-like slumber. For sooth!” she cried: “he must have seen me in this revolting state. He has put me to shame and has broken his solemn vow. Unfaithful wretch! I’ll make him suffer, for his perfidy.”

Then turning to the Hags of Hades, who attended her, she commanded them to give chase to him. At her word, an army of female demons ran after the Deity.

Translated by Yaichiro Isobe

Reference:

http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/world_civ/worldcivreader/world_civ_reader_1/kojiki.html

GoodReads

GoodReads