From ancient times to the present, the Japanese people have celebrated the beauty of the seasons and the poignancy of their inevitable evanescence through the many festivals and rituals that fill their year—from the welcoming of spring at the lunar New Year to picnics under the blossoming cherry trees to offerings made to the harvest moon. Poetry provided the earliest artistic outlet for the expression of these impulses. Painters and artisans in turn formed images of visual beauty in response to seasonal themes and poetic inspiration. In this way, artists in Japan created meditations on the fleeting seasons of life and, through them, expressed essential truths about the nature of human experience.

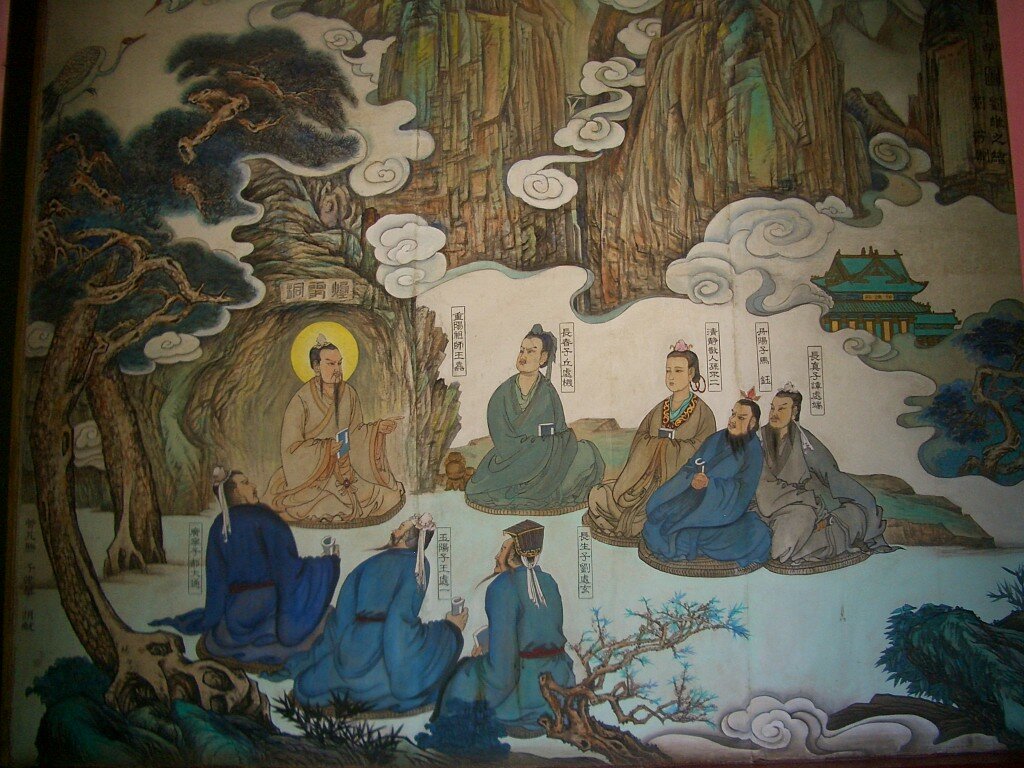

This sensitivity to seasonal change is an important part of Shinto, Japan’s native belief system. Since ancient times, Shinto has focused on the cycles of the earth and the annual agrarian calendar. This awareness is manifested in seasonal festivals and activities. Similarly, seasonal references are found everywhere in the Japanese literary and visual arts. Nature appears as a source of inspiration in the tenth-century Kokinshu(Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems), the earliest known official anthology of native poetry (rather than Chinese verse). These poems, produced by courtiers who embraced a highly refined aesthetic sensibility, not only celebrated the sensual appeal of elements of the natural world, but also imbued them with human emotions. Melancholy sentiments, invoked by a sense of time passing, loss, and disappointment, tended to be the most common emotional notes. This attitude can be seen in such visual arts as Buddhist and Shinto paintings of the Heian period that include lovely but short-lived blossoming cherry trees. Autumnal and winter scenes and related seasonal references, such as chrysanthemums and persimmons growing on trees that have already lost their foliage, are eloquent expressions of this same sentiment.

A distinctive Japanese convention is to depict a single environment transitioning from spring to summer to autumn to winter in one painting. For example, spring might be indicated by a few blossoming trees or plants and summer by a hazy and humid atmosphere and densely foliated trees, while a flock of geese typically suggests autumn and snow, and barren trees evoke winter. (Because this convention was so common, seasonal attributes could be quite subtle.) In this way, Japanese painters expressed not only their fondness for this natural cycle but also captured an awareness of the inevitability of change, a fundamental Buddhist concept.

The confluence of Shinto and Buddhism in the use of seasonal references demonstrates the central position of this practice in Japanese culture. As indicated above, cherry blossoms can be found in pictures illustrating Buddhist as well as Shinto concepts, with both expressing the beauty and brevity of nature. Similarly, folding screens decorated with ink monochrome paintings showing a transition from one season to the next initially were placed in the private quarters of Buddhist monks. Ritual implements and decorative items used in Buddhist temples and practice are often covered with flowers, birds, and other scenes from nature.

While the pictorial compositions that encompass all four seasons together present a broad view, more compact versions also appear. During the Momoyama and Edo periods, seasonal flowers and plants such as plum blossoms, irises, and morning glories became the entire focus of painting compositions. Similarly, decorative works such aslacquerware containers, kimonos, and ceramic vessels are frequently ornamented in this way. When natural elements are employed as decorative motifs, they are frequently stylized to heighten the ornamental effect. Once again, these visual scenes often have literary references, heightening the image’s mood and cultural meaning.

|

Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Resource: Here |

GoodReads

GoodReads