Kanamaruza Theater, a traditional kabuki theaterKabuki (歌舞伎) is a traditional Japanese form of theater with roots tracing back to the Edo Period. It is recognized as one of Japan’s three major classical theaters along with noh and bunraku, and has been named as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Kanamaruza Theater, a traditional kabuki theaterKabuki (歌舞伎) is a traditional Japanese form of theater with roots tracing back to the Edo Period. It is recognized as one of Japan’s three major classical theaters along with noh and bunraku, and has been named as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

What is it?

Kabuki is an art form rich in showmanship. It involves elaborately designed costumes, eye-catching make-up, outlandish wigs, and arguably most importantly, the exaggerated actions performed by the actors. The highly-stylized movements serve to convey meaning to the audience; this is especially important since an old-fashioned form of Japanese is typically used, which is difficult even for Japanese people to fully understand.

Dynamic stage sets such as revolving platforms and trapdoors allow for the prompt changing of a scene or the appearance/disappearance of actors. Another specialty of the kabuki stage is a footbridge (hanamichi) that leads through the audience, allowing for a dramatic entrance or exit. Ambiance is aided with live music performed usingtraditional instruments. These elements combine to produce a visually stunning and captivating performance.

Plots are usually based on historical events, warm hearted dramas, moral conflicts, love stories, tales of tragedy of conspiracy, or other well-known stories. A unique feature of a kabuki performance is that what is on show is often only part of an entire story (usually the best part). Therefore, to enhance the enjoyment derived, it would be good to read a little about the story before attending the show. At some theaters, it is possible to rent headsets which provide English narrations and explanations.

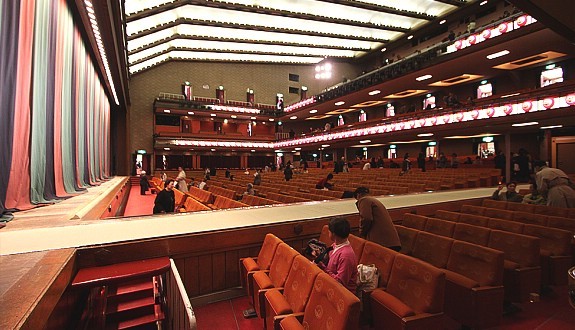

The interior of the previous Kabukiza Theater, a modern kabuki theaterKabuki conventions

The interior of the previous Kabukiza Theater, a modern kabuki theaterKabuki conventions

When it originated, kabuki used to be acted only by women, and was popular mainly among common people. Later during the Edo Period, a restriction was placed by the Tokugawa Shogunate forbidding women from participating; to the present day it is performed exclusively by men. Several male kabuki actors are therefore specialists in playing female roles (onnagata).

One of the things that will be noticed are assistants dressed in black appearing on stage. They serve the purpose to hand the actors props or assist them in various other ways, in order to make the performance seamless. They are called “kurogo” and are to be regarded as non-existent.

If you come across people from the audience shouting out names at the actors on stage, do not mistake this for an act of disrespect: all kabuki actors have a yago (hereditary stage name), which is closely associated to the theater troupe which he is from. In the world of kabuki, troupes are closely knit hierarchical organizations, usually continued through generations within families. It is an accepted practice for the audience to shout out the actors’ stage names at an appropriate timing as a show of support.

Formal dress code is not required when attending a kabuki play, although decent dressing and footwear are recommended. Sometimes, often on the first day of a run, some ladies dress in traditional kimono.

Rotating stage of a traditional kabuki theater from belowWhere to watch it

Rotating stage of a traditional kabuki theater from belowWhere to watch it

In the olden days, mainstream kabuki was performed at selected venues in big cities like Edo (present dayTokyo), Osaka and Kyoto. Local versions of kabuki also took place in rural towns.

These days, kabuki plays are most easily enjoyed at selected theaters with Western style seats. A day’s performance is usually divided into two or three segments (one in the early afternoon and one towards the evening), and each segment is further divided into acts. Tickets are usually sold per segment, although in some cases they are also available per act. They typically cost around 2,000 yen for a single act or between 3,000 and 25,000 yen for an entire segment depending on the seat quality.

reference: Japan guide

GoodReads

GoodReads